Just 30 years previously, Wolves were among Europe’s elite. Stan Cullis’ men were regularly playing the world’s best club sides in historic games under the Molineux floodlights.

Nobody could have predicted the state the club would have found themselves in by 1985.

These were desperate times in old gold. Dismal performances, dismal results, dismal attendances, and players wondering whether they would even be paid.

And things would get progressively worse.

With the club’s owners, the Bhatti brothers, facing severe financial difficulties, Wolves were loitering on the brink of going out of business, but fortunately, enough money was found at the 11th hour to keep the club from going the same way that so many have before and since.

However, the 1985/86 season took Wolves to their lowest ebb. Relegation to the fourth tier of English football for the first time in this famous club’s history.

More financial trouble hit in the summer of 1986. There was talk around this time that Wolves, one of the founding members of the Football League, could lose their status in the competition.

It was unthinkable, but almost became reality.

Thankfully, a last-minute deal saw Wolves sell off all its assets to the town council, Asda supermarket chain and Gallagher Estates Limited to keep the club afloat – but only just.

New manager Graham Turner was given the arduous task of turning around this once mighty football club. He set about it by calling on neighbours West Bromwich Albion and the cut-price signings of full-back Andy Thompson and striker Steve Bull.

As the season went on, more Baggies players crossed the Black Country divide; winger Robbie Dennison and defender Ally Robertson switched blue and white for gold and black.

Despite falling to Aldershot in the Division Four Play-Off final at the end of their first season in the basement of English professional football, the subsequent campaign was one of optimism – something that hadn’t been seen in Wolverhampton for the best part of half a decade.

“The club had had a tough couple of years and the fans will have despaired that a club of that size was competing in the old Fourth Division,” Turner remembers. “With the stadium being in such a bad way, it’d been neglected.”

“If there’s no fans, there’s no club,” stated striker Andy Mutch, who arrived at Molineux during the ill-fated 1985/86 campaign. “When I speak to supporters, they’ll never forget that resurgence. It was a phoenix from the flames story and all the supporters appreciated it after what had gone on in the past.”

The success Wolves were having in their second subsequent season in the Fourth Division saw the fans gradually return to a dilapidated Molineux. With both the Waterloo Road (now Billy Wright) Stand and the North Bank terracing falling into a state of disrepair, only two sides of the ground could be filled by supporters.

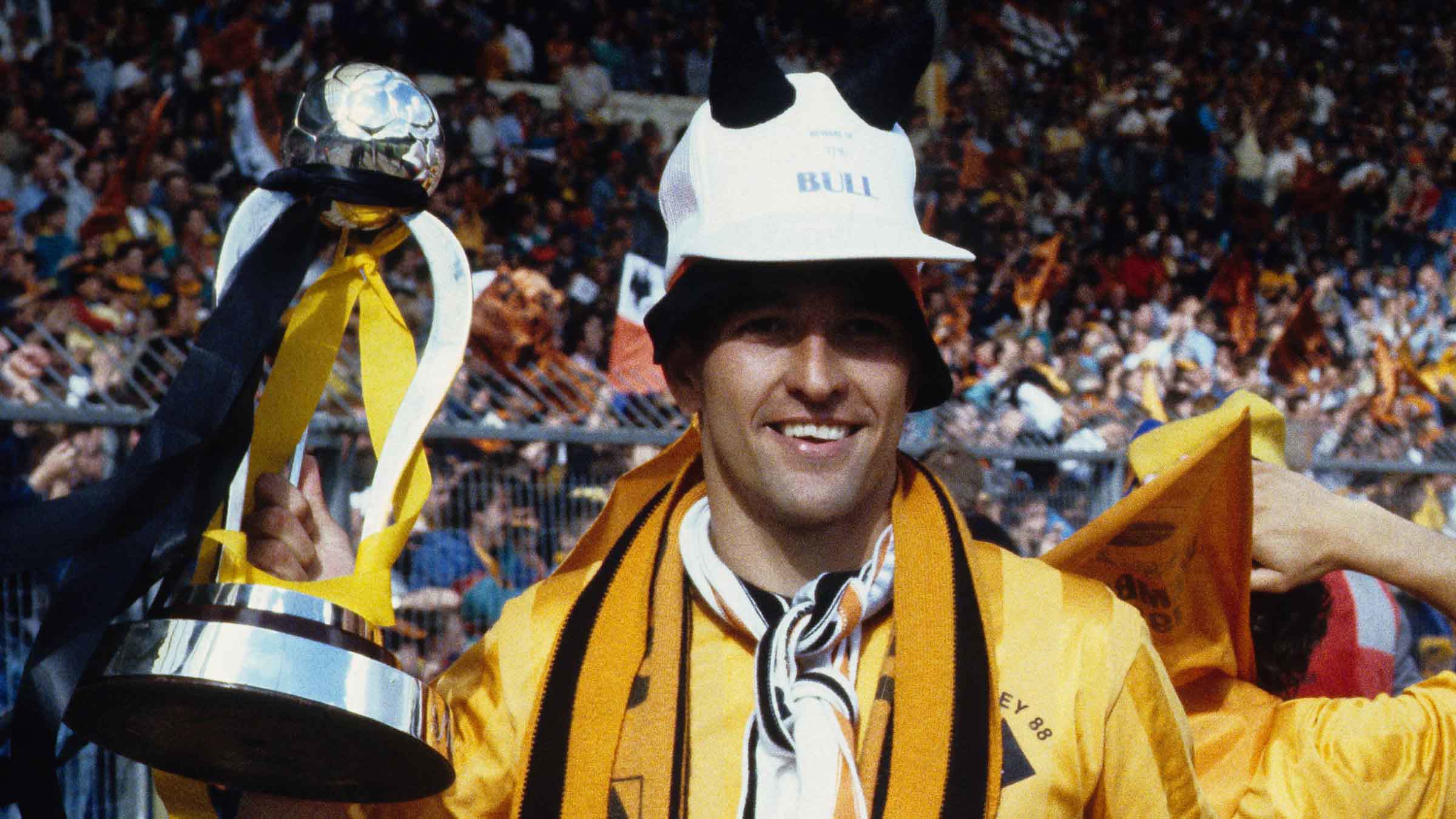

Having secured the league title thanks to Bull’s goals – 34 in the league and 52 overall, becoming the first player to top the half-century mark in a season since 1960/61 – Wolves had the chance to do a ‘double’.

Victories against Swansea City, Bristol City, Brentford, Peterborough United, Torquay United and Notts County saw Turner’s men reach the final of the Associate Members’ Cup (now known as the English Football League Trophy), or the Sherpa Van Trophy as it was called back then.

Exactly 32 years on from the final, Mutch recalls: “It was exciting for everyone involved, more so the supporters because they’re there forever. We got fantastic support which added to the excitement of the occasion.”

Scottish defender Robertson, who took over the captaincy after joining from those down the A41, remembers witnessing a sea of gold and black as the team travelled down to Wembley on the morning of the game. “It was incredible to see so many fans come to Wembley to watch us, it was brilliant.

“Although we had beaten Burnley during the season, we weren’t confident that we would do it again. It’s always one of those in the back of your head, ‘We’ve beaten them already, please don’t let them beat us today.’”

Between the league season ending and the Sherpa Van Trophy final, Turner rewarded his players for their efforts by taking them on a week in Spain.

The motto of ‘work hard and play hard’ was something that Bull recalls fondly, and that saying came into its own while out in the Majorcan coastal town of Santa Ponsa, when just a few hotels away, the players bumped into their Burnley counterparts, who they would go head-to-head with on the Wembley turf just days later.

“What made this game even funnier was that Graham Turner took us to Spain the week before, and Burnley were there,” Robertson said. “We had drinking competitions, we had everything, and we won the drinking competitions because Jackie Gallagher was the best drinker you could ever meet.

“So, when myself and [Burnley captain] Ian Britton were leading the teams out at Wembley, I looked at him and I says to him, ‘Well, we beat you at drinking, now we’ve got to beat you at football.’”

Many will recall the special atmosphere surrounding that game.

A then record attendance for the competition of 80,841 – which stood for more than 30 years and was only bettered during last season’s final between Sunderland and Portsmouth – demonstrated the significance of the occasion.

Although the majority would baulk at the thought of calling the competition a major trophy, try telling that to the players, staff and supporters of either Wolves or Burnley; two of the most historic clubs in the country who had fallen on hard times and were hoping glory in this final would relight their aims of getting back to the top, and where they belonged.

Turner admits: “I know it was the Sherpa Van, but it could have been the European Cup – it meant that much to us.”

“What was fantastic for me, was to join the club when the crowds here were down to two or three thousand,” Robertson added. “To see a club with so much history be in the position that it was and then, all of a sudden, we’re playing Burnley at Wembley in a cup final.

“Ok, it was the Sherpa Van, and people will say it means nothing, but that meant everything to the players and the club at that time.

“I remember standing in the tunnel and saying to the lads before we went out, ‘Lads, this is for those people out there.’ Because to look at the fans and see them, I said, ‘This is for them. We need to do this for them.’”

That importance reflected in the crowds, especially in the number of supporters who had travelled down to London from the West Midlands.

It has been estimated that almost two-thirds of the stadium that day were Wolves fans. More than 50,000 of them packed into Wembley to see their club, which less than two years previously was on the brink of extinction, rise from the ashes.

Bull, who would go on to play several more times at Wembley in subsequent years while wearing the three lions of England, recalls: “You wake up in the morning and are thinking about how many fans are coming down. Since I’d been at the club, they’d gone from 2,500 fans to 50,000, so it was bit nervy.

“On the coach was when the nerves really kicked in. I’d not played in front of those numbers before and when you saw the amount of gold and black in the stadium, it was brilliant.

“The only time you take it in is when someone gets injured and you have 30 seconds to have a look around. As a player you’re like a horse, you put your blinkers on. But I loved the day, it was brilliant for the fans because it put Wolves back on the map.”

It was a hair-raising moment for Dennison, who remembers walking out of the tunnel with a huge smile on his face and the feeling of being greeted by an almighty noise.

“Walking out at Wembley to more than 50,000 Wolves supporters was an atmosphere that made the hairs stand up on the back of your neck.

“By the time the game came around we were all ready for it, and it was made even more special when we found out that in a crowd of 80,000, more than 50,000 were Wolves fans – there were quite a few Wolves fans in the Burnley end!

“To get the opportunity to walk out onto the Wembley pitch at the end where the Wolves fans were, took my breath away. The noise was fantastic and it’s hard to describe the emotions you feel in that situation.

“Fortunately, I still have the photos at home from when I was walking out of the tunnel and have a massive smile on my face, and although I was nervous because of what I wanted to achieve with the club, I had to try and enjoy the occasion.”

Once the pomp and circumstance of Wolves’ first appearance at Wembley since the 1980 League Cup final was over, the game got underway.

It was the side in gold and black who made much of the early running and peppered the Burnley goal without really causing goalkeeper Chris Pearce too much trouble. And then, in the 23rd minute, the deadlock was broken.

After a couple of close shaves, a corner from the right was hooked back across the six-yard box by Bull for his strike partner Mutch to glide forward and glance a header into the back of the Burnley net.

“It was brilliant,” the goal scorer remarked. “If I’m honest, the occasion maybe takes over a bit. You don’t think too much about scoring at Wembley, you’re there to play the match and you’re worried about not winning.

“Anybody could have scored on the day, but it just happened to be me and Robbie D. That’ll be forever in my memory. I’ll always be privileged that I had the opportunity and took it.”

Following the half-time break, Wolves continued to put pressure on Burnley. Their offensive onslaught paid dividends in the 51st minute when Dennison majestically curled a free-kick past Pearce.

“Thankfully my goal put us 2-0 up and ended the game off as far as them trying to win it went,” insists the Northern Irishman. “We were always comfortable, but after that went in, there was no way Burnley were going to get back into the game.”

However, Burnley took over from that point, controlling much of the second period, but rarely threatened the Wolves back line, who were without their captain after Roberson went off injured.

Floyd Streete and Gary Bellamy were dominant in defence, so too was Mark Kendall between the sticks, being as safe as houses to keep everything Burnley could throw at him from going in the back of the net.

And even right at the death, Bull and Mutch both went close to adding to Wolves’ tally, with the latter striking the woodwork.

Reflecting on the ‘amazing’ emotions when the final whistle blew, Dennison said: “When you’re growing up as a football fan, you hear different things about what it’s like to play at Wembley, but for myself it was a stadium I always dreamed of playing at.

“We’d done well during the season and managed to get ourselves promoted out of the Fourth Division, we also had a good run in the cup – but for everybody in our team, our dream was to play at Wembley, and thankfully we had the opportunity to do that.”

While Turner felt his side thoroughly deserved the victory. “Robbie’s set piece expertise were once again crucial and it was roles reversed with Bully playing in Andy for the other goal. We’d hit the bar too.

“It was a huge honour to lead my team out at Wembley and win the trophy, made even more special because it was the club I supported as a youngster.”

Although delighted to captain the team to cup glory and earn the only trophy of his 21-year footballing career, Robertson was left disappointed by having to come off the pitch at half-time through injury.

“I was unlucky and absolutely gutted because I wanted to be there all the way through. But finishing my career by walking up those steps to pick up that cup was incredible.

“I looked at the game afterwards and we had all the game in the first-half, and when I came off, they seemed to have more chances in the second-half, but the lads did brilliant. Floyd and Mark – god rest his soul – were immense for us and there was no way Burnley were going to get back in it.”

Leading the team up the steps at the old Wembley holds a special place in the heart of the tough-tackling centre-back, who was able to pick out his family members he had invited down to the final as he was parading the trophy around the stadium.

“During my career, I’d been to three semi-finals and never got to a final. I was saying, ‘This is for them outside,’ when I was in the tunnel before the game, but it was also for me, because I wanted to win something, which is why walking up those steps meant so much.

“The only regret in my whole career is that I wish I would’ve been about two or three years younger, because we won the Fourth, the Third, and into the Second Division. I would’ve loved to have stayed with them a few more years to get into the old First Division.

“To finish my career doing that, would’ve been incredible.”

Getting to walk up to the royal box and put their hands on the trophy was just the first part of the celebrations for those Wolves players, with the merriment continuing long into the night.

A squad of players who liked a drink at the best of times were always going to enjoy the aftermath of a cup final win at the home of football.

“We were a team who always liked to enjoy ourselves; it was a great group of lads,” Dennison admitted. “I always believe that unless players get on with each other, then I don’t think they can be successful, especially at that time.

“If there was ever a chance for us to have a beer and some craic with each other then we would, and it was always good fun.

“After the final we stayed at the hotel together close to London with our wives and girlfriends and it was a fantastic celebration – which went on for a few days after.”

What greeted the players back in Wolverhampton the following day was something they had never witnessed before.

Thousands upon thousands of supporters lined the streets to show their appreciation of their new heroes bringing pride back to the name of Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Reflecting on that moment with much satisfaction, Robertson said: “What we couldn’t believe was on the Sunday, when we came back to Wolverhampton and went through the town, there were tens of thousands of supporters lining the streets – just like it was for the promotion to the Premier League a few years ago – and it just showed you what that trophy meant to the club and the fans.

“You didn’t realise how important it was. But it was great to see a club that was down on its knees, almost out of the game, to all of a sudden be back booming. It was a special time.”

A club that could have so easily have been reduced to nothing, despite being three-time Football League champions, four-time FA Cup holders, twice winners of the League Cup, was on its way back.

By adding a new piece of silverware to the Molineux trophy cabinet, it also meant Wolves became the first team in the land to win every domestic league and cup trophy possible.

A swift return to the second tier was to follow, with Wolves running away with the Division Three title the following season with virtually the same squad of players.

Once again, Bull was on tremendous form, rattling in another 50 goals to become the first player since 1928 to complete a century of goals in the space of two seasons, and earning the Tipton-born striker an England call-up.

But looking back at the day Fourth Division Wolves took 50,000 fans to Wembley, Turner understands the importance the match played in the future of the club, and how it changed the negative mindset at Molineux to allow Wolves to be the team it is today.

“I think it was huge. Winning at Wembley certainly played a massive role in the rebuilding job. It’s still spoken about to this day and I love going back to the former player events to discuss it and bring all the memories back.

“It’s the best moment of my time in football. It was my hometown club and was vital in the revival.”