Ahead of Wolves getting their 2022/23 campaign up and running this weekend, historian Clive Corbett has taken a look at one of the darkest of those days in Wolves history, which happened to have taken place 40 years ago this week.

***

In the summer of 1982, Wolves fans were not dwelling on a top ten finish in the top flight of English football, neither were they contemplating possible investment to strengthen the squad for a fifth Premier League campaign in succession.

A disastrous 1981/82 season had seen them finish bottom but one in Division One, bringing to an end a five-year stay there. But 40 years ago this week, Wolves were not only facing up to their fourth season out of the top flight since 1932, the club was also on the brink of a financial precipice.

Money problems, exacerbated by the building of the new Molineux Street stand, known by some as ‘Marshall’s Folly’, sparked a battle for control of the club as outlined in chapters 11, 12 and 13 of the splendid book, ‘The Doog’ by Steve Gordos and David Harrison. They write: “The £1.5 million outlay on the new Molineux Stand plunged Wolves into a cash crisis that would lead the club through the most traumatic decade in their history.”

As early as May, the Express & Star reported that the club had debts of around £2.5 million: ‘Sentence of death, but lawyers hope to appeal’, ‘Judge closes Wolves down’.

A revolt against the board of directors was led by Roger Hipkiss, a Wolverhampton born insurance broker, who is credited for gathering together a group of shareholders in an attempt to oust Marshall. Although a Wolves fan, he resented the fact that the chairman had got rid of his friend, John Ireland, seven years earlier. Derek Dougan, also harbouring a grudge against Marshall, for his peremptory interview for the manager’s post in 1978, remained in the background for now and was left off the list of names expressing no confidence in the regime at an Extraordinary General Meeting on the 8th June. This was partly done to avoid putting off potential supporters of the revolt.

Doug Ellis and Malcolm Finlayson were put forward as an alternative team in the event of the EGM leading to Marshall and his 80 year-old deputy, Wilf Sproson, being voted out. Fellow director George Clark, who had been on the board for 15 years, formally proposed the vote of no confidence, but Harry Marshall was not prepared to go quietly.

He admitted that the club was over £2 million in debt and losing £5,000 a week, with an extensive list of creditors including Birmingham City for non-payment of the £350,000 transfer fee for Joe Gallagher. Marshall outlined an alternative rescue plan that included selling the office block in the Molineux Street Stand to Walsall chairman Ken Wheldon for £500,000, the sale of Andy Gray, and the conversion of the Molineux Hotel into a supermarket. It was clear that a show of hands would have ousted Marshall, so he opted for a ballot of all shareholders that resulted in a narrow majority of 104 in his favour. On the basis of a claim that 500 votes were invalid, Hipkiss and the rebels issued a writ to overturn the vote, and on the 16th June Marshall resigned.

Ellis and Finlayson took over as chairman and vice chairman respectively, and within two weeks, an examination of the club’s books convinced them that there was no alternative but for Wolves to go into liquidation. Before this course of action was pursued, Finlayson personally loaned the club £370,000 and approached Sir Jack Hayward and others in an attempt to gather additional support. Although some still argued that liquidation would not be necessary since the club’s assets balanced its debts, on 2nd July Lloyds Bank appointed an Official Receiver, Alistair Jones, and an assistant, Alan Adam, from Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and company.

In those days, there would be no penalty of a points deduction, but if new owners could not be found before the end of July, the proud 105-year-old club would go out of business. The handing over of Wolves to the receivers in the summer of 1982 sparked off a bidding war that was believed to have involved, at various times, Robert Plant, Bev Bevan, Jack Hayward, Ken Wheldon and Doug Ellis himself. It was difficult to keep a sense of perspective that this was only football as the conflict in the South Atlantic drew to a successful close. Argentine forces on the Falklands Islands surrendered on the 14th June and their government eventually accepted defeat on 13th July.

Whilst the Falkland Islands conflict reached a successful conclusion, affairs at Molineux continued to rumble on. The receiver called a meeting at Wolverhampton Civic Hall to announce debts of around £2.5 million and confirm that the bank was owed £1.8 million, with daily interest charges amounting to £1,000 a day. Chesterfield Town rubbed further salt into the gaping wound by issuing a writ for non-payment of an instalment of Alan Birch’s transfer fee.

The Express & Star on Friday 9th July revealed the grim situation of Wolves’ finances, reflecting upon the events of a week earlier; “Wolverhampton Wanderers, one of the country’s leading clubs and a founder member of the Football league, went bust with debts of more than £2.5 million.” The receiver had put in place a four week deadline from that date to prevent Wolves from becoming the first major club to go out of existence since Leeds City in 1920.

The newspaper had obtained a copy of a previously confidential 60 page report, compiled by Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and company. Alastair Jones and Roger Dickens, working from Peat’s Birmingham office, listed profits for the previous four years as £175,000 (1978), £242,000 (1979), £306,000 (1980), £133,000 (1981). This was then followed by a massive loss of £650,000 in 1982 to that point, and two pie charts were used to summarise income and expenditure as follows; Income: match receipts 65%, executive boxes 15%, sub-contracted facilities 14%, donations 5%, other 1%; Expenditure: wages 47%, bank interest 20%, ground and administration expenses 18%, players’ expenses 15%.

Examples of players’ wages were given, including Joe Gallagher on £32,667, John Richards on £34,580, Andy Gray the highest earner on £49,255, and, by comparison young John Pender on a basic wage of £80 a week and £50 more every time he appeared in the first-team. Gray was reputed to earn more than the club accountant, secretary, commercial manager and first-team coach combined.

The catalogue of misery continued with a list of the club’s major creditors as of May 1982. They were as follows; Birmingham City FC £212,500, Chesterfield FC £90,000, the Inland Revenue £64,591, Customs and Excise (VAT) £30,136, West Midlands County Council £19,567, Molineux Street Stand contractors £16,541, PA system rental £1,213, Players’ travel £1,171, and water rates £1,088.

It was reported that four groups were involved in rescue plans, led by Harry Marshall, Jack Hayward, John Bird and Ken Wheldon. As the wheeling and dealing continued, the beginning of the next week was marked by the bizarre news that Michael Fagan had spent ten minutes in the Queen’s bedroom in Buckingham Palace. On July 17th first-team coach Ian Ross walked out on the club to join John Barnwell on the rebel tour of South Africa, despite being refused permission to do so by the receiver. The day before the deadline, Thursday 29th July, saw the official publication of Lord Snowdon’s photographs of Princess Diana and her baby William, who had been born on the 21st June.

The Express & Star announced that Walsall chairman Ken Wheldon was putting the finishing touches to his takeover bid, a deal apparently supported by Jack Hayward. The Black Country scrap metal merchant was in negotiation with Alan Adam, although there was new competition from a Manchester based consortium formed by Doug Hope, a long-time acquaintance of Derek Dougan, and another group led by Rotherham’s Chairman Anton Johnson. According to David Harrison, the Doog’s backers were unknown for several weeks until they were tracked down by Express & Star reporter, Derek Tucker. A Manchester based friend of Hope, Mike Taylor, had put him in touch with John Starkey, an architect involved with Allied Properties.

Hope brought Dougan on board for meetings with Starkey, Taylor and another Allied director Mike Rowland that eventually involved Mahmud and Akbar Bhatti. The Bhatti brothers were not Saudi Arabian as was first indicated but a couple of Pakistanis working out of a portakabin at Manchester Airport and who had purchased Allied Properties for £10,000 a year earlier. They were to put in £500,000 of their own money and borrow the rest from Lloyds Bank using the club as collateral. In response to this Vice Chairman Doug Ellis announced that his group’s bid, supported by former player Malcolm Finlayson, had been increased from £1.15 million by £300,000 on Thursday evening.

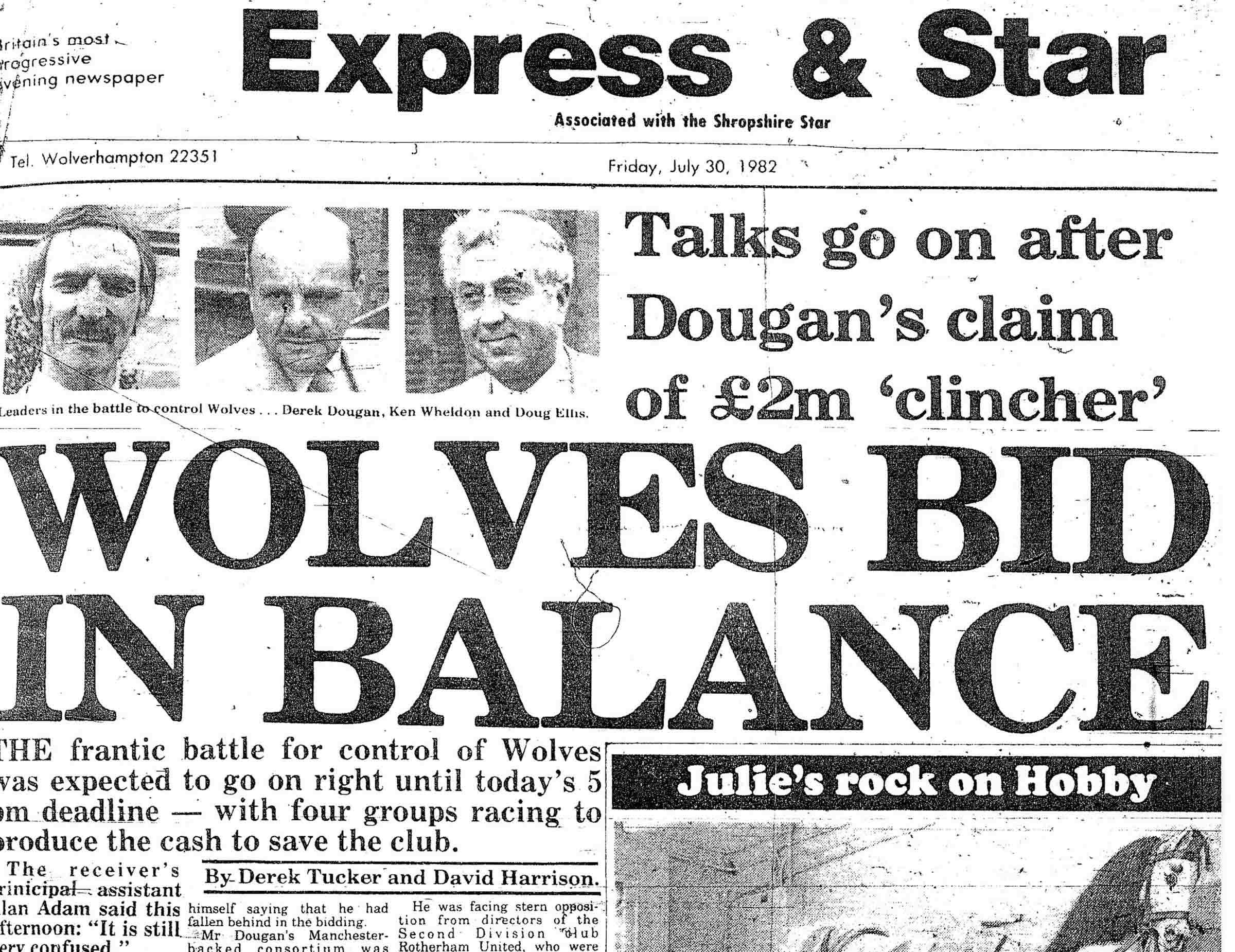

As the final day of bidding dawned, on Friday 30th July, Derek Tucker and David Harrison monitored the situation for the Express & Star: “The frantic battle for control of Wolves was expected to go right on until today’s 5pm deadline - with four groups racing to produce the cash to save the club.” Early in the day Derek Dougan claimed that his group had clinched the deal with a £2 million bid, but Assistant Receiver Alan Adam declared: “It is still very confused”.

The Doog was bullish though: “We have reached an agreement in principle with the Receiver and are hoping to finalise it before this afternoon’s 5pm deadline. We have made an offer in excess of £2 million in cash, which was the sum required. We have achieved something of a miracle. We only came into the race last Friday and in six days we have moved a mountain. We have taken on some formidable opposition and I am 99 per cent certain we have beaten them.” Later in the day Ken Wheldon seemed to accept the fact: “It looks as though we are not going to get it. This is not going to become a Dutch auction.”

Geoff Palmer graphically recalls those tense final moments of Friday 30th July: “In the summer, we were five minutes from going out of business. It was a bad time, you didn’t realise how serious the situation was. It was a hell of a shock, there were rumours going round in the papers, I thought, bloody hell! You always think somebody will buy it, there had been so many people interested and all of a sudden it’s the last Friday and nothing’s been done. You’re glued to your radio with five minutes to go. What was I going to do? I’d never been in touch with the PFA. What would we do if the club goes bump?”

Derek Parkin, who by then had joined Stoke City, was shocked but not really surprised: “I didn’t know the ins and outs of the football club but could sense that there was something not right. Ian Greaves had warned me that it was time to get out because the club was going under. It was sad because it needn’t have happened, but I did know they were struggling. We all got bold together and they didn’t recoup any money for the players.”

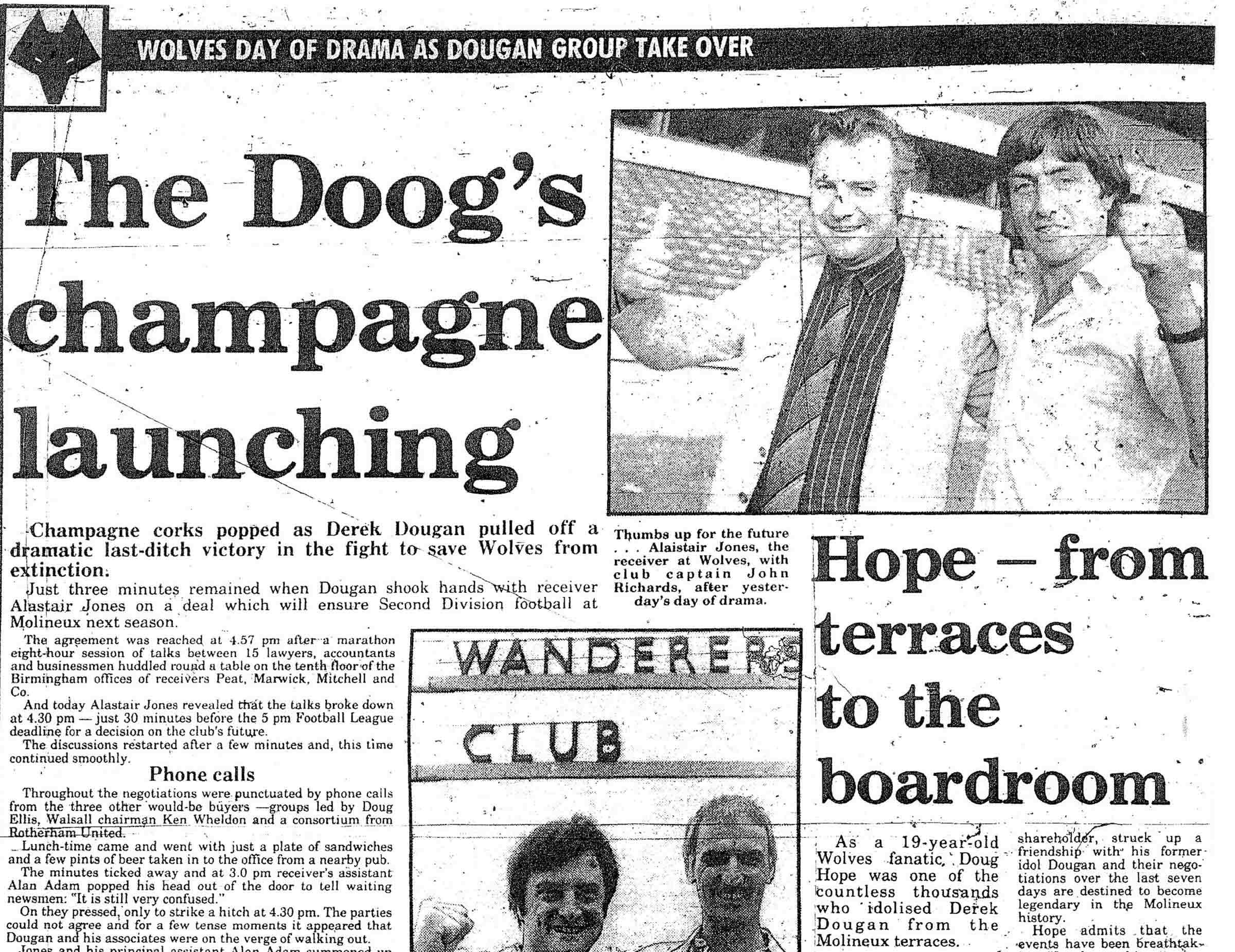

On the day of the deadline, Doug Hope and the Doog were in the offices of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and company in Birmingham and their £1.8 million bid was accepted with just three minutes to spare, beating off a rival bid of £1.65 million from Doug Ellis, Ken Wheldon, and Jack Hayward. As Dougan confirmed, it was indeed at 4.57pm that they signed off guarantees of £50,000 to the Football League: “That was how close Wolves were to going under, and Doug Hope and I are proud to think that we have played our part in securing the well-being of a club which is very close to our hearts.”

Public confirmation came in the next day’s Express & Star, under the headline ‘The Doog’s champagne launching’. It was revealed by Receiver Alastair Jones that talks briefly broke down at 4.30pm, but then re-started in time for completion of the £2.5 million deal at 4.57pm. It completed a marathon session of eight hours that involved 15 lawyers, accountants and business advisers around a table on the tenth floor of the Birmingham office of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and company.

Jones admitted: “It really was touch and go to the very last. But, thankfully, we have managed to secure a very favourable deal for the creditors of Wolverhampton Wanderers.”

It was also reported that over £3,000 worth of season tickets had been sold in the first four hours of the new regime and the euphoria of the takeover. Doug Hope, described as moving from the South Bank to the boardroom, was introduced as a key figure in the consortium. The Scot, who had first come to Wolverhampton as a sales representative for a tyre company in 1965, could hardly believe the turn of events: “I woke up this morning and wondered whether it had all really happened.”

In the first week of the new regime, manager Ian Greaves and commercial manager Jack Taylor were both asked to resign and, on refusing, were sacked. Mel Eves recalls the departure of the manager, who had come close to keeping Wolves up after John Barnwell had left: “I had an awful lot of time for Ian Greaves, if he’d had more time we would have stayed up. He was such a good man manager and we were really playing for him. At the end of the season the Bhattis came in, and the Doog had a run in with Ian before. It was nothing to do with Ian Greaves, he was collateral damage in the takeover.”

According to Steve Gordos, Greaves had indicated exactly this to John Richards during pre-season training just before the takeover: “‘If Dougan comes here, that’s me finished.’ John Richards thought that they had clashed on a TV panel and continued; ‘Within a few days of Derek taking over, Ian Greaves was gone, making me think straight away that if you upset Dougan, he won’t forget it.’”

Muriel Bates maintains that both Greaves and Jack Hayward suffered from Dougan’s spite: “Jack had bought a box for all the destitute children, but Dougan stopped him having that and turfed him out. I knew Dougan because I was working for Mr Clift, a friend of his. Dougan told me if he got the club Ian Greaves wouldn’t be there although he was getting that team round. So Graham Hawkins dropped into Ian Greaves’ slot, if you upset Dougan that was it. While Dougan was doing that he was putting on bills for breakfast at the York Hotel, champagne breakfasts every morning and billing it to Molineux.”

After four years at Molineux, Jack Taylor sought advice over legal compensation: “I feel very sad, I have been involved with the club since I was 16 and I would like to think that considerable progress has been made since I took over as commercial manager.” Andy Gray, who was the subject of constant speculation over a move from Wolves, was hardly shocked by the change of manager: “I’m not really surprised. Everyone at the club more or less expected that. I had a good working relationship with Ian Greaves and I’m very disappointed he hasn’t been given the opportunity to see his job through.” He went on to discuss his own future, having been most recently linked with Manchester United: “It’s no secret I want to get away and I will be speaking to the Chairman as soon as possible to let him know my feelings.”

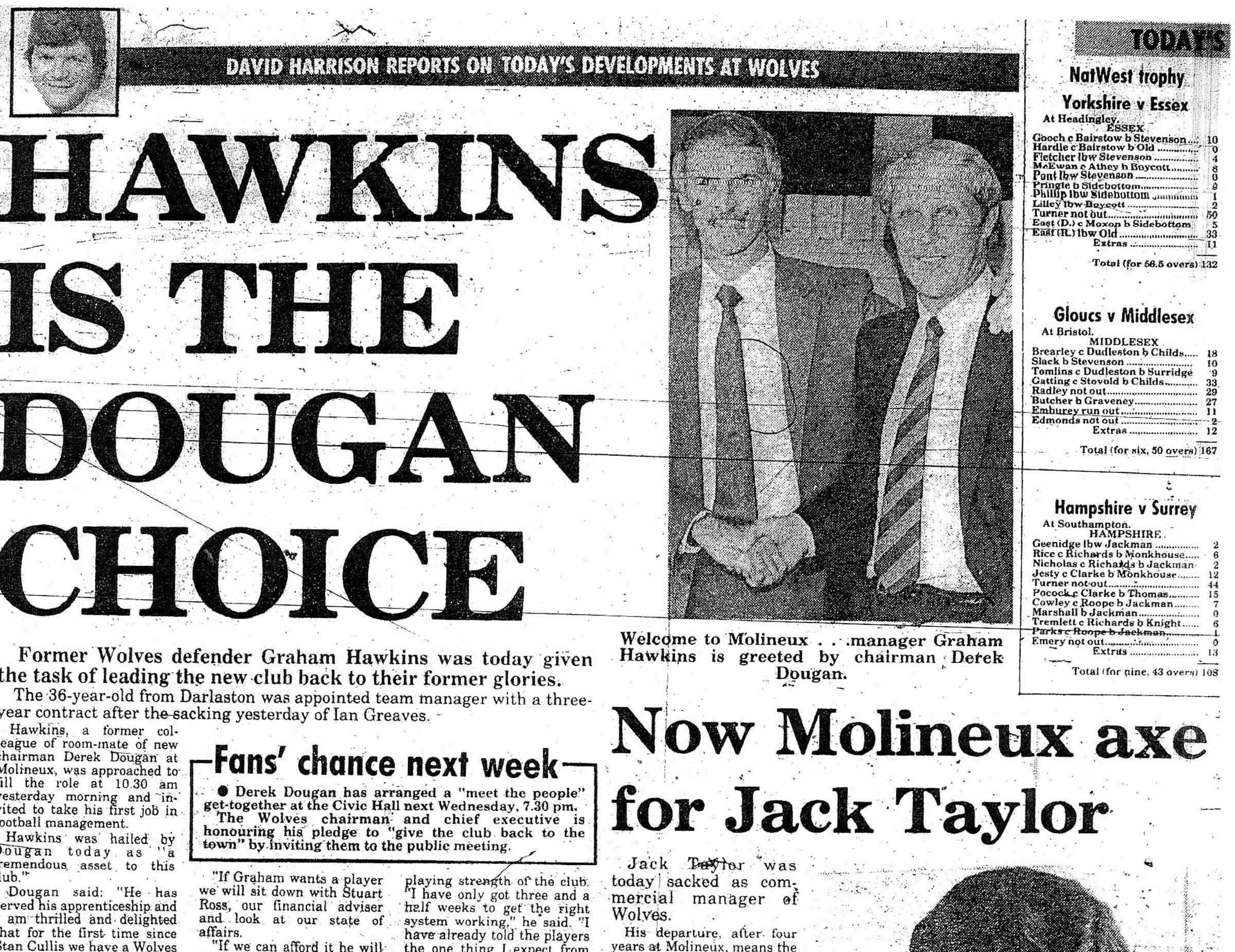

Although the Express & Star had reported that Graham Turner was favourite to fill the managerial vacancy, Graham Hawkins was given a three year contract on Wednesday 4th August, the day of Prince William’s christening. Dougan welcomed the new boss: “He has served his apprenticeship and I am thrilled and delighted that for the first time since Stan Cullis we have a Wolves man as manager at Molineux. I would like to think he knows this division like his two hands. It is an unknown territory for us and I believe Graham’s knowledge will be a tremendous plus factor. Whatever he says and does he does so in his own right and in his own way. If Graham wants a player we will sit down with Stuart Ross, our financial adviser, and look at our state of affairs. Likewise, no player will leave this club unless the manager says so, not Derek Dougan.”

The 36 year-old from Darlaston appreciated Dougan’s assurances: “I will be totally in charge of team affairs from the first team and scouting to the schoolboys. I have only got three and a half weeks to get the right system working. I have already told the players the one thing I expect from them is to give me 100 per cent. Now I want to see Wolves return to the place they belong. Derek says they are one of the top ten teams in the country, but I would put them higher than that.”

Hawkins had joined Wolves’ ground staff in 1961 and made 34 first team outings between 1964 and 1967. He outlined his Wolves credentials: “I’ve reflected on it since, but nobody has been in the position I was in. I’ve been a fan, apprentice, player and manager. A bus ride from Darlaston, paid my two shillings or whatever to get on to the South Bank.”

So, Wolves were saved 40 years ago this week, and Graham Hawkins went on to lead them to promotion from Division Two at the first attempt. However, he did not receive the financial backing promised in the summer of 1982 when, exactly a year later, he took a shopping list to Dougan that included David Seaman, Paul Bracewell, Mick McCarthy and Gary Lineker.

Little did we know then that there was no money and that the Official Receiver would be called in again in July 1986 as Wolves faced a nightmare descent to Division Four.

But that's another story...